Shakti Pith #47: The Mahishamardini Mandir of Bakreshwar

Bakreshwar: A Conflux of Shaiva and Shakta Tradition

Although Bakreshwar, West Bengal is primarily renowned for its Shiva temple and therapeutic hot springs, these attractions tend to overshadow its parallel significance as a place of power for goddess devotees. As a shakti pith, the Mahishamardini Mandir draws worshipers of the divine mother to this country town, named for its resident male god. At the heart of Bakreshwar, the spiritual traditions of Shiva and Shakti converge, reconciling the dichotomy of masculine and feminine divinity in one harmonious temple complex.

Historically a focal point of religious pilgrimage, the majority of Hindus traveling to Bakreshwar come for its famous Shiva Mandir. Although the presence of a shakti pith and its corresponding mandir (Hindu temple) technically make Bakreshwar a two-temple complex, the veneration of Lord Shiva observably assumes a position of elevated prominence.

Unlike the red vestments typical of Brahmins officiating at temples consecrated to Shakti, the preferred color of Bakreshwar’s dhoti (unstitched men’s garment) clad priesthood is white. When I asked one of these Brahmins about this idiosyncrasy, he attributed it to a belief that the Shiva Mandir was older than the temple of Mahishamardini. Given the lack of an accurate and comprehensive written record, such a statement could easily be written off as hyperbole. Factual or not, the casual utterance of this claim reaffirms the primacy of Shiva worship at this temple complex. It is a sentiment that I repeatedly encountered during conversations with many Bengali people who were well acquainted with Bakreshwar as a seat of Shaiva tradition, yet unaware that it was also the location of a shakti pith.

Deviating from typical Bengali style, the Bakreshwar Mandir, with its distinctive curvilinear shikhara (rising tower above the sanctum sanctorum), and the surrounding complex evince a strong Orrisan architectural influence. The inner sanctum, which houses the lingams associated with Shiva and the sage Ashtabakra, is accessed through a roofed, tunnel-like corridor. A steel guardrail runs along the center of this passage, effectively separating it into two pathways, and thus making it easier to manage occasional larger crowds. An assortment of brass bells are chained to this divider and––coupled with the resonant properties of the tiled chamber––can be heard echoing throughout the day and night, as they are periodically rung by devotees entering and exiting the garbhagriha (Sanskrit for “womb chamber;” the inner sanctum).

The name Bakreshwar is a compound of two words: bakra, meaning “curve” or “deformity,” and ishwar meaning “lord.” According to local legend, it was in the vicinity of the Bakreshwar Mandir that a crippled sage, named Ashtabakra (“eight curves”) Muni, intensely meditated upon Lord Shiva for 10,000 years. Profoundly moved by this ardent display of penance, Lord Shiva not only cured his beloved devotee of physical deformity, but further declared that those who visited Bakreshwar and venerated Ashtabakra before him would be graced with a surplus of boons. Corresponding with this myth, there are two lingams housed within the Shiva temple. The larger lingam is referred to as Ashtabakra, and the smaller one is called Bakreshwar. Although specified with different names, both of these lingams are perceived as physical manifestations of Lord Shiva which, by extension, function as conduits of spiritual power through which the god can be communed.

Bakreshwar’s inner sanctum is a small enclosure having four walls which are tiled in white ceramic and a floor of marble slab. In the center of this room, a concave yoni (Sanskrit “vagina,” symbolic as creative source) is set more than a foot below floor-level. The yoni’s interior is gilded with a brass-like metal and where it meets the floor it is framed with segments of marble. It is constructed to slope in a slight descent toward a drainage hole in the northern wall. Projecting upward from the center of the yoni’s rounded lower half is the sacred lingam of Ashtabakra. This stone formation is sheathed with a fitted cylindrical covering made from the same metal which lines the yoni. I was informed by a temple Brahmin that this is in fact a special alloy known as ashtadhatu––an amalgam of eight symbolic metals: gold, silver, copper, zinc, lead, tin, iron, and mercury. Crafted by the same artisan, this very specific composition was also used for casting the Mahishamardini murti which is enshrined in the neighboring goddess mandir. Analogous to the crippled body of the legendary saint, Ashtabakra, the stone lingam which is concealed here is said to bend at eight different points along its length. Visitors do not get to see the unsheathed lingam, but I was told that its covering is periodically removed for ritual bathing of the stone. As this is a highly-cherished lingam, it receives regular oblations in the form of flower and bael leaves, libations of water and milk, as well as incense and candles which are lit and placed around the yoni. Such a profusion of offerings easily obscures the much smaller Bakreshwar lingam which is directly adjacent to Ashtabakra.

Initially, I had wrongly assumed this to be a one lingam temple and thought that the encased lingam was Bakreshwar––an easy mistake to make during a first visit. It was while offering a puja (ritual offering ceremony) in this mandir that I learned of the coexistence of another lingam. During the ceremony, I was instructed to touch both of the lingams with my right hand. Probably sensing my confusion, my Brahmin friend Partha continued to intone Sanskrit mantras while brushing off a pile of marigold flowers and bael leaves that had buried the sacred stone. Then he took my hand and guided it inside the yoni, toward the base of the Ashtabakra lingam, where I touched a smooth, rounded stone. Bakreshwar’s eponymous lingam is a small, polished rock formation that barely projects outward from the base of the yoni in which it is nestled. Over the course of centuries, an incredible amount of tangible power has manifested through this ostensibly humble embodiment of the divine. The Bakreshwar lingam is the foundation upon which this extensive temple complex has developed and, by extension, the pivot of an entire township consecrated in one of Shiva’s holy names. Not only have diverse spiritual seekers from every corner of the subcontinent been attracted to this place of power, but foreigners like myself come here from distant countries around the globe.

Hot Springs

Bakreshwar is the site of several geothermal hot springs, some of which are believed to have healing properties. Throughout its history, people suffering from a spectrum of afflictions have sought relief by coming here to bathe in these mineral-rich waters. Many of the smaller springs are bounded by concrete retaining walls, in a quasi-rectangular configuration resembling a stylized yoni, with descending steps on one open side permitting access to the water. The two largest stepwells are surrounded with a gated wall and function as the primary “public baths” of Bakreshwar. The unique geothermal activity not only effects the enclosed springs, but much of the water found in this area. Locals and visitors swim in the lake on the complex’s southern side throughout the cool season as its water remains continuously warm. During my first night at Bakreshwar, I waded across a creek (always advisable when in an unfamiliar place!) and was surprised to find the water pleasantly heated, despite the air temperature being cold enough for me to see my breath. A painted sign on the main temple gate lists the following eight springs:

1. Agni Kund 2. Khar Kund 3. Bhoirob Khund 4. Shoubhaga (Dudh) Kund

5. Shurjo Kund 6. Shwet Ganga 7. Papohora Ganga 8. Jibotsha (Amrita) Kund

On the northern side of the complex, directly in front of the Shiva mandir, is the Shwet Ganga. One of Bakreshwar’s larger pools, it is rectangular in shape and walled round with red brick. This is a highly-frequented kund as it is routinely used by pilgrims for ritual purification baths prior to entering the mandir for puja. The water of the Shwet Ganga is not only perfectly lukewarm, but remarkably clean since it is not stagnant. Grates built into the walls of this kund allow the water to freely flow through it.

Two other kunds I will briefly comment on are referred to as the Dudh Kund and Agni Kund. The word dudh means “milk” and the water of this smaller kund has the unique quality of taking on a pale white color during the early morning hours before sunrise. I was not able to determine exactly why this phenomenon occurs, but suspect it has something to do with the interplay of a high ozone concentration and minerals present in the water.

Another remarkable spring is the Agni Kund, or “Fire Pond.” Its water is very hot, reaching temperatures that approach 200 degrees Fahrenheit. The steps of this kund have been sealed off and a protective wall surrounds it. A temple priest told me that as a boy, he once witnessed the removal of a scalded, dead human body from the Agni Kund. Apparently, this kund has been the site of occasional suicides where people have leaped over the wall and plunged directly into its boiling depths. Adjacent to the Agni Kund is a building which houses a government-run laboratory. Upon inquiry, I learned that fluctuating concentrations of various gasses in the water are monitored by this lab, and the resultant data is used to detect seismic changes. During my daily visits to the Mahishamardini Mandir, I would walk past the Agni Kund where I regularly observed a man fetching water from it using a length of rope attached to a metal bucket. This pail was then briefly put aside, allowing the water to cool before it was poured into one of the plastic bottles he had arranged on a folding table. Calling out to passersby, he offered draughts of this water for a few rupees per drink. Naturally curious, I asked him what the purpose of drinking this water could be. Rubbing his stomach, he informed me that it was an invigorating tonic for the whole body and implored me to try a sip, free of charge. Despite his enthusiastic endorsement of this water as a salubrious elixir, I had no way of knowing if it was indeed safe to consume, and respectfully declined his offer.

When I stayed at Bakreshwar, the two main bathing springs were undergoing renovation. Although I did not get to see them in action, I entered this private area and walked around while construction was taking place. The ground is paved with decorative tile and terracotta friezes depicting health-related themes drawn from Hindu religious sources, beautify the surrounding walls. There are designated entrances for men and women, who bathe in separate kunds. Further enhanced with amenities such as shower stalls, changing areas, and public restrooms, these hot springs are being developed into an attractive focal point of Bakreshwar tourism.

Other Places of Interest

Now a relatively modest temple complex, Bakreshwar once received royal patronage and this prior state of affluence is evident in its surroundings. Scattered throughout the vicinity are hundreds of small concrete temples, housing in-built Shiva lingams, which have fallen into varying states of decrepitude. The extensive range and number of these mandirs suggests that a sizable priesthood was once employed here, charged with ritual veneration and maintenance of these shrines when they were still active.

Close to the main mandir is a panchamukhi asana (seat of five skulls), an area specifically constructed for the performance of tantrik sadhana (ritual practices). Although appearing to be a nondescript red concrete platform, underneath of it the skulls of five different animals, including one human, are buried in a carefully arranged manner. According to tantrik belief, the power of sadhana is increased when performed on a panchamukhi asana and I was strongly cautioned against casually sitting here.

Bakreshwar is also home of the Bashudeb Mission International, a philanthropic religious institution founded by the highly-esteemed Bengali Shaiva sadhu, Bashudeb Paramahamsa. In the mission’s courtyard, a magnificent “Lingam of Fire” towers at nearly eleven feet tall and weighing around 8 tons. It is carved from a single mass of imported white Carrara marble and embellished with flames containing stylized yoni shapes.

Throughout its long history, Bakreshwar has been regarded foremost as a place of healing. People suffering from diverse ailments have journeyed here, seeking physical respite in the hot springs and divine grace through the temples. With an imminent renaissance on the horizon, Bakreshwar is now entering its own state of convalescence. Enhanced by extensive renovations and developments, the influx of religious pilgrims coupled with a blossoming health-conscious tourism industry will bring with it increased interest and funding. Difficult work lies ahead, but a feeling of excited anticipation permeates the air as Bakeshwar begins a phase which local residents hope will not only restore, but eclipse its former glory.

Mahishamardini Mandir

Located close to Bakreshwar’s preeminent Shiva temple, the Mahishamardini Mandir is discernible by the bright orange shikhara towering above it. This mandir can be reached from the main entrance of Bakreshwar Road, which first brings you to the Shiva temple. From here, a short walk heading west along the jagati (raised platform upon which a temple rests) will take you to the goddess temple. If you wish to go straight to the Mahishamardini Mandir, there is also another entrance located on the southern side of the complex, which provides direct access. There you will ascend a flight of steps and enter the orange and yellow gate which leads to the platform directly in front of the mandir and darshan with its south-facing murti.

The temple’s wooden double doors are notable for being ornamented with six hand-carved friezes. Lakshmi, Saraswati, Ganesha, and Kartik are separately depicted in each of the upper four sections. Below these, the tripartite assemblage of coconut and palm tree in a water pot, broadly connoting “good luck,” is rendered as a matching pair. This three-fold symbol is simply called ghatam, meaning “pot.” In Bengali iconography, the goddess Durga is often accompanied by this cluster of four deities who are commonly referred to as her “children.” Mahishamardini is one of many names for Durga and although the murti which is enshrined here depicts her unattended, the presence of her typical retinue is acknowledged with these carved images.

A few feet away from these doors is the temple harikhat, a sacrificial device employed in the immolation of goats. The harikhat is essentially a wooden fork into which a goat’s neck is placed and secured with a pin. The animal is then easily decapitated with a single chop from the khadga (ritual sword) in the sacrificial rite known as boli. This harikhat is painted bright red, the color of shakti––or feminine power.

The name of the goddess revered here, Mahishamardini, is a well-known epithet of the goddess Durga. It is composed from the Sanskrit words mahisha, meaning “buffalo,” and mardini, “the slayer.” This particular appellation thus refers to the goddess’ mythological role as destroyer of the buffalo demon named Mahishasura or Mahisha. Within the garbhagriha of this mandir, a small shrine, carved from marble, rests atop a rectangular pedestal and houses the sacred image of Mahishamardini. This murti is a cast metal sculpture in high relief depicting the goddess, accompanied by her lion vahana (animal vehicle), thrusting a spear through the heart of the demon Mahisha.

The goddess is ten-armed, symbolically expressing the omnipresent nature of her power; but aside from the spear wielded with one hand, she is otherwise without her typical assortment of weapons. Holes in the nine remaining clutched fists allow visiting devotees to add a personal touch to their puja by placing a miniature tin weapon––available in the nearby shops on Bakreshwar Road––in one of her hands as an offering. The murti itself is not very large, perhaps standing about three feet tall altogether including the attached base and background. According to a temple Brahmin, this murti is ashtadhatu––made from an alloy of eight metals that have astrological significance.

As with every shakti pith I have visited, I gave offerings to the local goddess as a gesture of gratitude. With the assistance of my Brahmin friend, Partha Paitandi, I gave a lengthy and thorough puja at Bakreshwar; beginning first with the two sacred lingams of the Shiva temple, then the local “protector” Botukbhairav, and finally to Mahishamardini. Partha recited Sanskrit mantras as we ritually offered the goddess an assortment of incense, flowers, sindoor (red pigment powder), decorative bangles, fruit, and libations of water. The evening before this puja, I was asked to choose a weapon to place in one of the goddess’ hands as a symbolic offering. For me, this was an easy decision: I chose the khadga (ritual decapitation sword), preferred weapon of my ishta devi (patron goddess), Kali, which through various synchronicities has become a personal symbol of my spiritual path. A photograph of Mahishamardini holding the khadga I offered her accompanies this essay.

Shakti Pith

The temple dedicated to Mahishamardini is not only the home of an asthadhatu murti, but the forty-seventh shakti pith traditionally listed in various manuscripts such as the Mahapithanirupana. Like every other shakti pith that I have visited, the presence of the locally-revered goddess at Bakreshwar is expressed in a two-fold manner: revealed and concealed. While most of the religious pilgrims visiting this temple come to venerate the ashtadhatu murti, there is more to this place than what initially meets the eye. It is within the pedestal upon which the murti rests that the source of this locale’s designation as a shakti pith resides.

Within this mandir, a metal gate creates a buffer where the Brahmins can perform their rites in front of the murti while separated from the throngs of devotees who periodically arrive in large numbers; either on holidays, or as groups completing a temple circuit. During periods of relaxed temple activity, or upon special request (often accompanied with baksheesh––an encouraging monetary tip), one can enter the garbhagriha and approach the murti.

Since I stayed in Bakreshwar during an “off season” while the hot springs were undergoing renovation, temple activity was relatively lax and I was able to enter the inner sanctum on several occasions. The first time I visited this mandir, a Brahmin led me through a side door and directly into the garbhagriha. While I was offering pranam (salutations) to the murti, he directed my attention to a circular hole, a little over a foot in diameter, on top of the marble pedestal. This hole provides direct access to the adi rup (original form) of the local goddess: by placing a hand inside, one can touch the goddess’ bhru moddo, or the space between her eyebrows. Reaching in, I felt a stone formation; its outer surface is smooth, round, and wet from the libations regularly poured into it. In the center of this hollow circular space, the rock juts upward. Sliding my hand along the surface of this projection, I was able to discern that it resembles a crescent with rounded edges.

In many popular images of Hindu goddesses, the place between the deity’s eyebrows is ornamented with a lunar crescent. This is not merely an aesthetic embellishment emphasizing the goddess’ transcendent beauty, but also symbolizes the power she wields over time itself––attributable to the moon appearing as a crescent shape throughout its repeating cycles of waxing and waning. The obvious correlation between the shape of this adi rup and the recurrent moon motif leads me to believe that such commonly heard claims as this temple housing Sati’s “third eye,” “forehead,” or “mind” are the result of misconceptions pertaining to a relatively obscure body part. My tactile experience confirmed that the designation of “portion between the eyebrows” found in the Mahapithanirupana is correct. Within the Mahishamardini Mandir, a stone formation corresponding in shape to the ornamented portion of flesh between the Mahadevi’s eyebrows, her bhru moddo, is enshrined and venerated.

The Cremation Ground

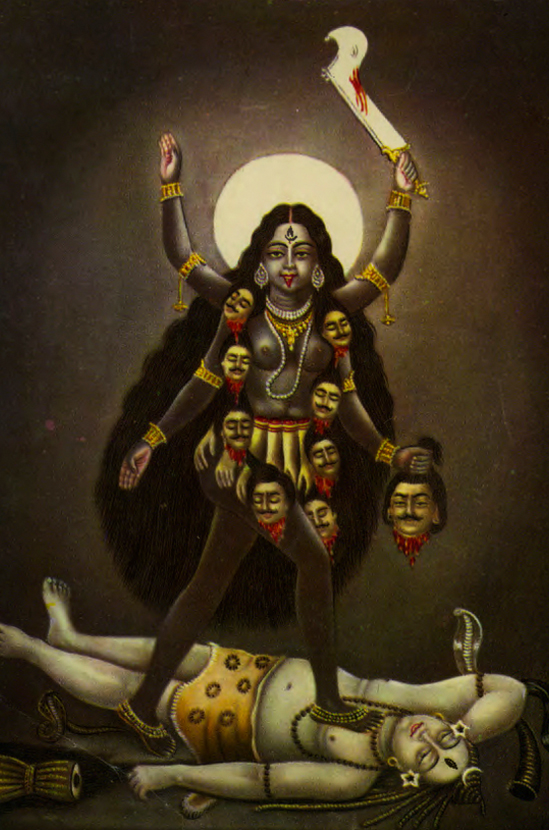

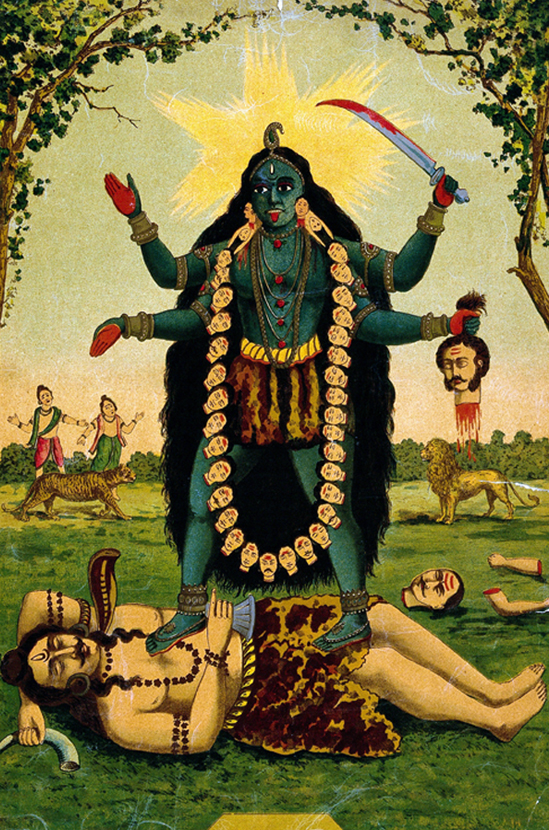

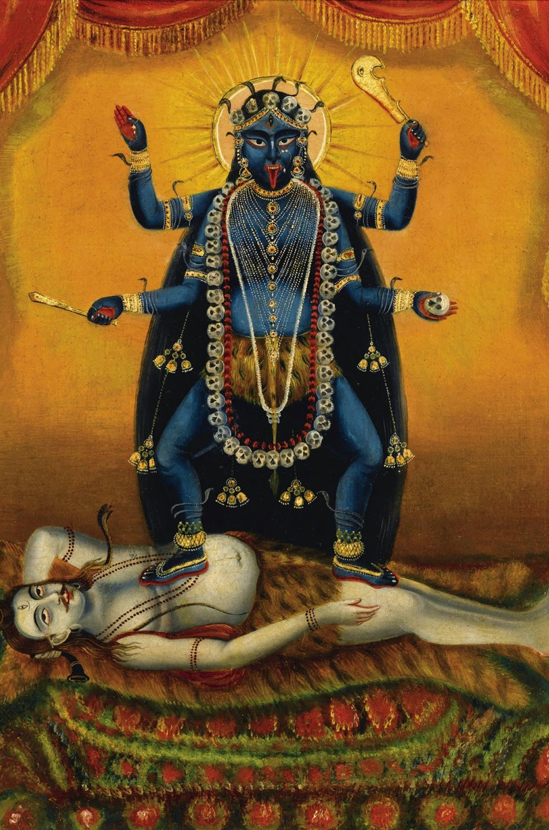

A narrow, unpaved road beginning near the main temple complex guides you along a winding path flanked on opposite sides with a motley arrangement of grave markers. As you approach the cremation ground’s main entrance, a small roadside temple presents itself. The phrase “JAY MA SMASHANA KALI” (Victory to Mother Kali of the Cremation Ground) is written above its doorway in bright red Bengali script. Housed within this shrine, a murti of Kali depicts her standing upon her husband––Lord Siva––in characteristic pose, brandishing a sword and holding a severed head with her left hands while her right hands give the mudras (symbolic hand gestures) of abhaya (fear not) and varada (conferring boons). Although essentially depicting the dark mother goddess in her popular form, a few macabre embellishments have been added here to emphasize the particularly fierce nature of her smashana (cremation ground) aspect. Wavy red lines, flowing from the corners of her mouth around her cheeks and down her neck, have been painted to represent oozing blood. On Kali’s left and right sides, two semi-nude female shaktis (human embodiments of transcendental feminine force) gaze upward toward her as they dance, both of them smeared with gore and feasting on human flesh.

Bakreshwar’s sacred burning ground is separated from the surrounding area by a border of tombstones and a brook running along the side of it. Cremation here differs from others I have observed in that a network of connected trenches is employed to contain the improvised wooden pyres. The resultant fire, burning at ground level, is thus easily managed by the Dom who use bamboo poles to manipulate the wood and break the body down as it is slowly incinerated. Pieces of wood which have not burned away are removed, put aside, then later incorporated into fresh pyres.

To be cremated at Bakreshwar is considered particularly auspicious, so it follows that this burning ground is a highly active one. Dead bodies routinely arrive, not just from the local community, but also from various locations throughout West Bengal, and even as far away as the neighboring states of Bihar and Jharkhand. During my daily visits, I often witnessed up to five pyres burning at the same time. The soil here is permeated with ash, imparting it with an overall gray cast, and where the river runs directly alongside the cremation ground, its water is almost black.

Much of my time at Bakreshwar was spent interacting with the local Dom who seemed just as eager to hear stories of my life in America as I was to learn about their unique occupation. The cordial hospitality of the Dom contrasted with the immediate gloomy environment. While seated amidst blazing funeral pyres crackling all about, I found myself regularly being offered tea and snacks. Together, we would also frequently indulge in the more ill-advised pleasures of smoking bidis (tobacco-leaf wrapped cigarettes) and ganja (Sanskrit word for cannabis), as well as quaffing copious amounts of bangla––a local rice-based moonshine. I have many fond memories of the Bakreshwar smashana; despite it being a place of death, I mostly recall the friends I made, along with the laughter and good times we shared.

An event in particular still stands out in my mind as being one of the most distinctive experiences of my travels thus far. Early one morning, I visited the smashana where I encountered a small group of Dom gathered together near a single burning pyre. One of the men greeted me and was excited to find I could converse in Bengali. He brushed off a tombstone and offered me a seat beside him to talk. A chai wallah (tea seller), standing nearby with a kettle in his hand, was immediately called over. My new friend then pointed at the funeral pyre (with a clearly recognizable human corpse burning on top of it), said a few words, and the tea pot was placed directly into the fire. As we chatted over that warm cup of chai, I thought of how bizarre this entire scenario would seem to most folks I know back home. Death is an inescapable aspect of life which people generally confront only when forced to do so. For most of us, it remains safely hidden away until it ultimately appears––seemingly out of nowhere––to rear its ugly head before once again returning to the shadows. For the Dom however, there is nothing at all unusual or shocking about the atmosphere of the cremation ground. Dealing directly with the grim reality of death is just another day on the job.

When reflecting back on the time I spent at Bakreshwar, I will always remember Korno, a twenty-one year old young Dom man who I became close friends with. Over the course of my stay in India we forged a bond that I suspect will last the rest of my days. It was because of Korno that I was able to experience as much of an inside view of Dom life as could be hoped for during a brief stay. A tantalizing angle for pursuing further research into the mysteries surrounding Kali crystallized during an afternoon ganja session we shared near the cremation ground.

On this day I visited the smashana and found it surprisingly empty, a rather infrequent occurrence allowing the Dom free time to enjoy some respite from their work. While wandering about, I chanced upon a group of Dom sitting with a Tantrik (practitioner of magical arts) and was asked to join them. As a freshly-packed chillam (cylindrical clay pipe) was passed around, we were discussing more mundane matters when Korno asked me if everyone in the USA followed Christian dharma (ancient word referring to universal order, used here in the common sense as “religion”). I explained that while the majority of Americans are Christian, there is a mixture of spiritual beliefs reflecting the diverse population. He then asked if I was a Jishu bhakta (literally “Jesus devotee”) as well. When I responded to this question by stating that I am a bhakta of Kali, the group became visibly elated. Waving his hand in a circle, Korno enthusiastically proclaimed that everyone in the group was also a bhakta of Kali. He then added with a friendly smile, “Kali is one of us, she is a chandala!” This word “chandala” comes to us from Sanskrit, originally as a designation for outcaste people whose occupation is the disposal of corpses. In modern times, it is commonly used as a pejorative to slander people as low, filthy, or generally despised.

In all of my encounters with the Dom, I have invariably found them to be devotees of the archetypal dark mother goddess Kali, or the closely related Ma Tara. As a liminal deity associated with the social periphery and cremation ground, Kali would seem a fitting patron for the Dom––members of a stigmatized caste traditionally considered “untouchable” by mainstream society. However, it appears counterintuitive that within a patriarchal and caste-oriented social system, the image of a low-caste female would be widely venerated as the ideal anthropomorphic representation of the cosmic matriarch. Kali the mother, as we know her today, is a multifaceted deity who undoubtedly developed through the synthesis of myriad indigenous goddesses whose roots reach back into prehistory.

It is not unreasonable to assume that the modern Dom descend from a tribal group who were subjugated at some point in the distant past. Relegated to the lowest rank of society, such a vanquished people would naturally take their patron goddess with them as they moved about, engaging in occupations determined by their caste. Although the origins of Kali may forever remain obscured by an impenetrable veil of mystery, I believe that a key to shedding a modicum of light upon her shadowy evolution lies within the seemingly parallel saga of the Dom. My own experiences have consistently affirmed that a profound connection exists between the black mother and this stigmatized caste which venerates her. It is an intriguing relationship that I feel obliged to investigate and make the focal point of future research. Through photography, field recording, and writing, I hope to share some of my discoveries and revelations as the outward, tangible reflection of an essentially internal, spiritual journey while I dedicate my life to exploring the Kali mythos––wherever she may guide me.

A Note on the Recordings

My experience of Bakreshwar was greatly enriched by the generous assistance of Partha Paitandi, a Bakreshwar Brahmin. During my stay, Partha guided me to sacred sites throughout the town while eagerly sharing his extensive knowledge of Bakreshwar’s rich history. We bonded through our mutual love of music and when I explained to him the nature of my Shabda Brahman project, he offered his enthusiastic support.

One evening, Partha surprised me with a trip to the nearby town of Tatipara, famous for the production of silk. Shortly after arriving, I was introduced to a man named Bappi Sinha. A school teacher by profession, Mr. Sinha is not only a refined connoisseur of music, but a talented artist himself. Unbeknownst to me, he had arranged for a group of musicians to gather at his Tatipara home where I was treated to what turned into an inspired house concert which lasted well into the early morning hours. A tremendous amount of fun was had by all and this event was unquestionably the highlight of my stay. The majority of recordings I am sharing here were made that night.

This musical ensemble consisted of the following individuals: Bapi Sinha – Vocals & Harmonium, Kalipada Sen – Vocals & Harmonium, Subal Das Baul – Vocals and Khamak, Dhananjoy Bhattacharya -Tabla, Somnath Chakraborty – Harmonium, Sohodeb Bauri – Flute, and Jhantu Bauri – Percussion. Many thanks goes to these men; their generosity is greatly appreciated.

The last recording came about by chance. I was returning from the Bakreshwar temple complex during the early evening hours when I heard song and music coming from a small building. Not one to let a good recording opportunity pass by, I immediately set up my gear, stepped inside and tried to position myself to capture the sound as clearly as possible. My enthusiasm for Bengali folk music and ability to keep proper time with a pair of kartala (small metal hand symbols) earned me the good graces of all who were present. Afterward, everyone had a great time passing around the digital recorder and headphones, taking turns listening to the songs I recorded.

5 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- put on its water-garment | KAJORI - [...] When I was writing those above haiku Bakreshwar was all that in my mind. One of my cousins is…

Comment

Wonderful article! Who but the Doms , like Kali can happily inhabit the cremations ground. Thank you for throwing light on the psysocial meaning of “shmasaanavaasini” and why Kali is often called a “Dombi” or “Chandali”.

excellent write up.a visual treat.

Love to reading your artical. Jay ma kali

Very well written travelogue, gripping, till the end