Shakti Pith #19: Kalighat Kali Mandir

Early medieval accounts of the shakti piths (centers of power) cite Kalighat as the dwelling place of a particularly fierce manifestation of the goddess, known as Dakshina (“south-facing”) Kalika. Once surrounded by a dense jungle and accessed primarily by boat, this riverside abode of the Cosmic Mother has transformed into a bustling temple complex, located in the heart of one of India’s largest and most populous cities. At the Kalighat Kali Mandir, the dark goddess who has been worshipped since time immemorial continues to reign over this nexus of power where the ancient and modern worlds intersect.

DAKSHINA KALIKA: GODDESS OF THE CROSSROADS

Located in one of Kolkata’s oldest neighborhoods, Kalighat is a renowned center of goddess worship and place of pilgrimage, where devotees have come for centuries to surrender themselves at the feet (literally) of the Divine Mother. Local folklore relates that Kalighat, once a jungle region, was inhabited by head-hunting tribal people and Kapaliks (“skull-bearers”) who worshipped the dark goddess with human sacrifice. Mythologically, such references to “tribal people” and outcasts are often employed to assert Kali’s position as a marginal goddess who exists outside of the societal fold. Although the origins of this shakti pith are obscured in myth, allusions to an important Kali temple in this area date from the middle of the 12th century and it cannot be argued that this place has a direct association with Kali from ancient times (Roy 16).

The Haldar family, who have traditionally comprised the goddess Kalika’s priesthood, cite two important factors contributing to Kalighat’s preeminent position among the shakti piths. The first which is given relates to its location. Worship of the goddess at Kalighat is paired with that of Shiva at the nearby lingam temple, it is located near a cremation ground, and it is adjacent to the Adi Ganga river. Secondly, this shakti pith is associated with the goddess’ feet where the toes of Sati’s right foot are said to have fallen, making it the penultimate place of submission for her devotees (Basu 17). Recurring expressions of crossing over, duality, and surrender are found repeatedly not just in the mythology of Kali, but also in the area of Kalighat and throughout this essay. Such themes include: crossing over from the realm of the immanent to the transcendent, embodied in this locale by its cremation ground and its proximity to flowing water; the union of opposites, displayed in the masculine/feminine dichotomy of Shakti and Shiva, as well as complimentary rites centered around both purity and blood-letting; and finally, surrender to the goddess who is ultimately perceived as the Cosmic Mother. It is the last theme, that of surrender, which circumscribes the rest.

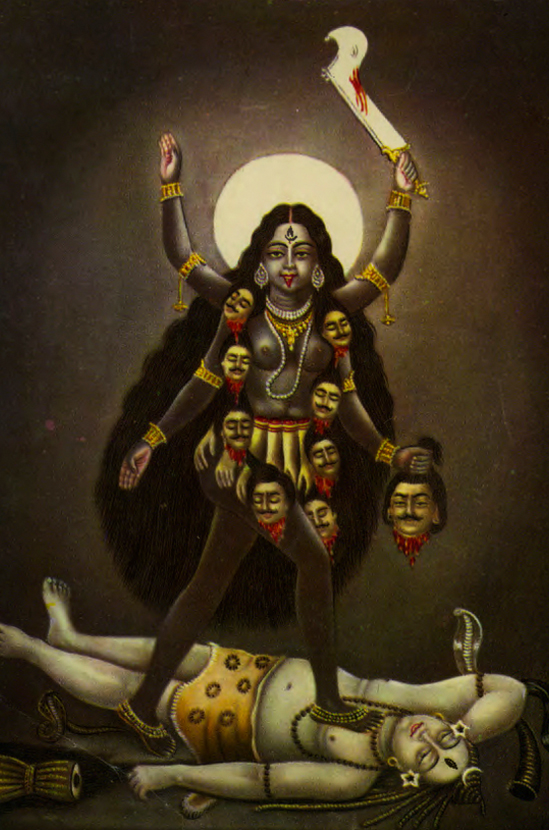

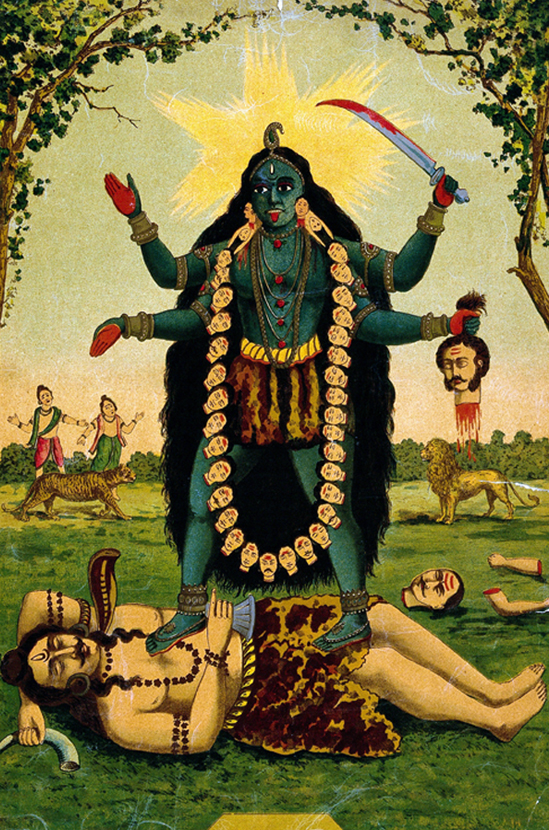

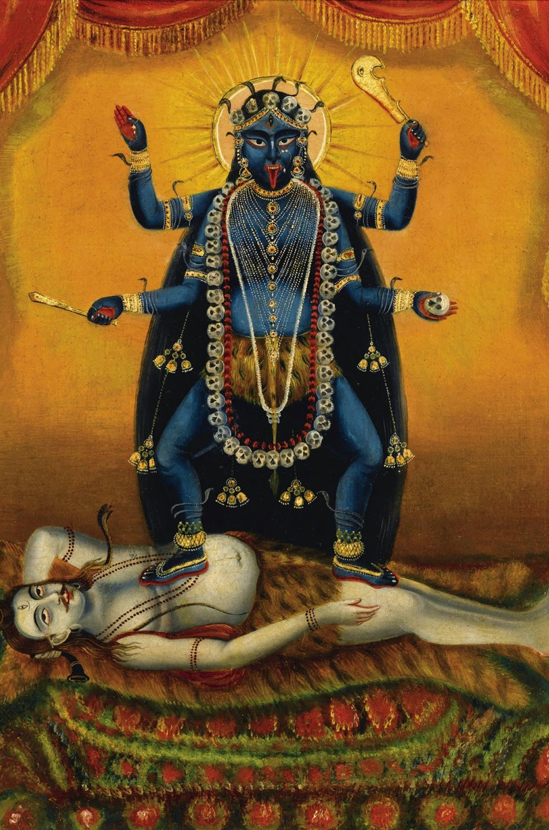

While Kali embodies the harsh consequences of life––aging, pain, struggle, and death––she is simultaneously viewed as the source of all earthly sustenance and spiritual salvation. These radically different dimensions of Kali’s multivalent personality might at first seem to contradict one another, but it is important to remember that the name Kali––besides referring to her darkness––is the feminine form of the Sanskrit word kala, meaning “time.” Our perception of life and the universe is invariably based upon our experience of existing in time, and the changes we continually undergo until we die. It is Kali’s role as the transformative power which underlies her diverse representations. Never depicted in a state of stillness, she is the eternally dancing Kali whose sinuous motions are the ebb and flow of nature––evident in the alternating cycles of creation and destruction, day and night, birth and death. Kali not only encompasses all of nature’s complimentary aspects, but as the supreme Mother Goddess, transcends them. Although Kali the Mother is widely venerated throughout India and abroad, she is particularly popular in West Bengal where she is worshipped in a myriad of forms. The city-dwelling businesswoman of Kolkata (who views the divine through the Universalist lens of Vedantic philosophy) and the rural Adivasi tribal woman (who communes with the village-specific genius loci of an earthen hut temple), even though they occupy distinct social spheres and appear to revere completely unrelated deities, might nonetheless both address their patron goddess as Kali.

At the Kalighat Kali Mandir we find a mixture of diverse religious expressions––ranging from the “orthodox” rites of Brahminical Hinduism to spiritual practices aligned with the folk Shakta tradition of the villages. Animal sacrifice is a regular affair and the occasional Tantrik can be spotted wandering around the Kali Mandir, carrying a human skull and offering his magical services for a price. During one visit, I was profoundly moved by the sight of a man sitting cross-legged in an alcove adjacent to the temple. The assistant priests who pointed him out informed me that he was in the midst of a trance state. Gazing in the direction of the murti, his eyes looked white from being completely upturned into the back of his head. His body slowly rocked in a circular motion while his lips constantly moved as if he were speaking. It was a striking look that I have seen once before. Back in 2004, I visited the town of Bishnupur, West Bengal, to witness a festival in honor of the snake goddess, Manosha. I had wandered to a village on the outskirts of town, where I was invited to attend a local sacrificial ritual called boli. Accompanied by the sound of loud drumming, I watched in awe as goats were repeatedly beheaded and their blood consumed by the local priests. One by one, people around me became possessed by Manosha, their eyes rolling backward as they fell to the ground writhing like snakes. It was a compelling experience that I will never forget. Because such passionate, visceral religious experiences are common among the village folk, to see a similarly intense display of communion at Kalighat was a powerful reminder of the goddess Kali’s tribal roots. Her connection with provincial rituals and practices endures, even in midst of one of India’s most cosmopolitan cities.

THE ANCIENT GODDESS AT THE HEART OF A MODERN MEGACITY

Kolkata, affectionately nicknamed “the City of Joy,” is a major metropolis which surges with a population of over 14 million people. This vibrant megacity is not only regarded as one of India’s most important cultural epicenters, but proudly boasts of significant international contributions to the arts. A diverse array of influential personalities such as the poet Rabindranath Tagore, saint Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, filmmaker Satyajit Ray, Catholic missionary Mother Theresa, and the freedom fighter Subhash Chandra Bose are just a few of the many iconic figures claimed by Calcuttans as their own.

This same city was the capital of India throughout most of the period of British rule, officially retaining the anglicized spelling of ‘Calcutta’ until 2001 when it was changed to ‘Kolkata’ as a closer approximation of Bengali pronunciation. This name ultimately derives from that of the fishing village Kalikata, which previously existed in the vicinity of today’s Kali temple. The former village’s name––Kalikata––is a Bengali permutation of the Sanskrit Kalikshetra, meaning “Field of Kali.” Aligned in both name and spirit, Kolkata is widely regarded as “Kali’s City,” and her tangible presence here is ubiquitous. Within the city’s limits, there are three major temples dedicated to Kali: Adyapith, Dakshineswar, and Kalighat. Roadside shrines in the upscale, touristy shopping districts of Central Kolkata house murtis of the dark mother, and traveling about the city by cab will reveal that many taxi wallahs (generally meaning “provider,” but used here as “driver”) maintain dashboard altars dedicated to one of her forms. And while most of India celebrates the autumnal “festival of lights” known as Deepavali, the frenzied atmosphere of Kolkata gives way instead to an explosion of creative pandal (temporary stages) displays and fireworks, signaling the arrival of Kali Puja, Kali’s annual day of revelry.

A far cry from its humble origins, the number of daily visitors to the Kalighat Mandir are commonly estimated to run into the thousands (Gupta 62). As a site of major historical influence, Kalighat is always listed as an important destination in Kolkata tourist guides and is now easily accessible to the masses who flock here, arriving by car or train. In spite of its widespread popularity, the Kalighat Mandir still maintains an aura of impenetrability as often-repeated stories of local corruption, the priesthood’s notorious demands for money, and misconceptions surrounding the ancient practice of animal sacrifice serve to keep the resident deity, Kalika, obscured to all but the persistent.

KALIGHAT’S INTRICATE SOCIAL WEB

Much like the goddess who is venerated here, Kalighat has an ambivalent reputation. Foreign tourists as well as Indians often describe their visits in negative terms, and nearly every person in KoIkata with whom I spoke about Kalighat complained of how the temple affairs are managed. A perusal of tourist guide books and websites will elicit a number of harshly critical reviews, mostly regarding the demands for money by people often mistakenly identified as “priests” of the temple.

A vast, complicated social hierarchy of people depend upon the Kalighat Mandir for their subsistence. Most of them are not officially employed by the temple, but nevertheless meet their economic needs through adeptly hustling the steady influx of unwary pilgrims who arrive here every day. At the lowest social tier are the dalals, who function as freelance brokers for the local shops. As you approach the mandir (Hindu temple) from Kalighat road, you are accosted by these men whose authoritative mien and traditional attire often confuse people into thinking they are temple Brahmins, although they have no real authority within the temple. These self-proclaimed “guides” promise a quick darshan (“sight”) of Kalika which they claim is only possible with their assistance. Before bringing pilgrims into the temple, the dalals typically walk visitors about the marketplace, encouraging them to buy puja (ritual worship) items such as flowers and sweets from shops which in turn pay these brokers commission. The dalals lead the hapless devotees inside the temple complex to take their darshan––an activity which the pilgrims could have just as easily accomplished by themselves. These unsanctioned escorts will then attempt to charge an exorbitant fee for what was actually an essentially useless service.

Occupying a social standing above that of the dalals are the unionized Brahmins known as pandas, whose original occupation was to serve as guides for non-local visitors. The pandas come from different parts of India, speak a variety of languages, can perform basic rituals, and usually know a lot about the temple. Although their services (or anyone’s for that matter) are by no means required, many people choose to employ the assistance of the pandas. So, while the dalals are purely an extension of the marketplace, the pandas have a closer relationship to the religious life of the temple. Furthermore, their occupation is based upon heredity, with some of the current pandas descending from families which have served at Kalighat for several generations, conferring upon them a marked degree of credibility.

Ranking higher than the pandas and closer to the actual central authority of the Kalighat Mandir is the phaledar, or temple treasurer, accompanied by his chosen team of delegates who handle all of the monetary donations received by the temple. The role of phaledar is a revolving position––the individual who fills it is appointed on a daily basis. This rotating phaledar and his assistants are notorious for requesting large sums of money from visitors, and have even been known to bar people from exiting the Kalighat Mandir’s inner sanctum while demanding payment.

At the highest rung of the Kalighat social ladder is the Haldar family. Ownership of the Kalighat Mandir and associated property rests exclusively in their hands. The Haldar family are the shebaits of Kalighat, a title which means that they not only own the entire temple complex, but are also the official pujaris who conduct and perform the daily rituals.

Although I was aware of Kalighat’s complex social web and warned about elements of corruption well in advance by my Bengali friends, I decided to hire the services of a dalal in order to observe their method of operation for myself. After purchasing fewer puja items than I was encouraged to, I was quickly led about the temple premises and taken into the natmandir (large pavilion), where I was told to give the offerings while facing the direction of the Kalika murti. He became argumentative when I refused to pay any more than a token fee for his nearly worthless “services,” but he finally relented and hurried off to continue his job with other new arrivals. For me, this was a rather amusing spectacle, but it is easy to understand why people would feel disappointed in their visit to the temple after getting taken for such a ride. I am very lucky to have been able to visit Kalighat regularly enough to avoid such pitfalls, but for the people who come once, only to find themselves tricked into paying unnecessary fees and coerced into giving excessive donations, it is understandable how their view of this holy place could be soured. There is no obligation to pay anything when visiting Kalighat, and a much better darshan of Kali can be obtained on your own after waiting some time in the queue to see her from the jor-bangla (viewing area) passageway’s closer proximity to the murti. The dalals and pandas approach everyone heading toward the mandir, and are used to being turned down; they will back off with a firm, yet courteous refusal of their service. It is also possible to enter the garbhagriha (inner sanctum) for darshan directly in front of the murti, but a respectful donation is the norm in this case.

During my last trip to India, I spent five months living in South Kolkata which gave me ample opportunity to visit Kalighat on a frequent basis. I found that my experience improved dramatically with regular visits. Over time, I became a familiar face to many people employed at the temple and working in the local shops. Yet despite the sense of familiarity which developed, I was no match for the staggering network of people employed in and around the temple. I was never immune to requests for large donations from phaledars and associates who had not seen me before, or the dalals who would incessantly approach with offers to guide me to the Kali Temple. It was a routine that became an increasingly comical expectation as I began to think of Kalighat as my own place of spiritual refuge, where I could feel removed from the “big city” life of Kolkata. Once, while I was receiving darshan in the jor-bangla, gazing upon the Kali murti with my hands clasped together in prayer, a young man wearing a dhoti, stepped directly in front of me and enthusiastically proclaimed “This is goddess Kali!” I laughed at what seemed like such an obvious affirmation––I could not imagine finding myself in the crowded jor-bangla of the Kalighat Mandir, being pushed about by a throng of eager devotees, and yet completely clueless as to what the place was or who I was praying to. The Kalighat Mandir is not exactly renowned as a place of quiet contemplation and must be accepted on its own terms.

As a site of historical importance, which is directly linked with the founding of Kolkata, Kalighat is a popular destination for tourists. Many foreigners who come to the temple are quickly overwhelmed by the apparent chaos which surrounds it and turn away, feeling confused or let down. For the intrepid, Kalighat can be a place offering an incredibly rewarding spiritual experience as well as insight into the complex relationship between an ancient place of religious pilgrimage and the socioeconomic demands of modern city life. I would not hesitate to recommend a visit to Kalighat with the caveat that a little foreknowledge of its inner workings can go a long way.

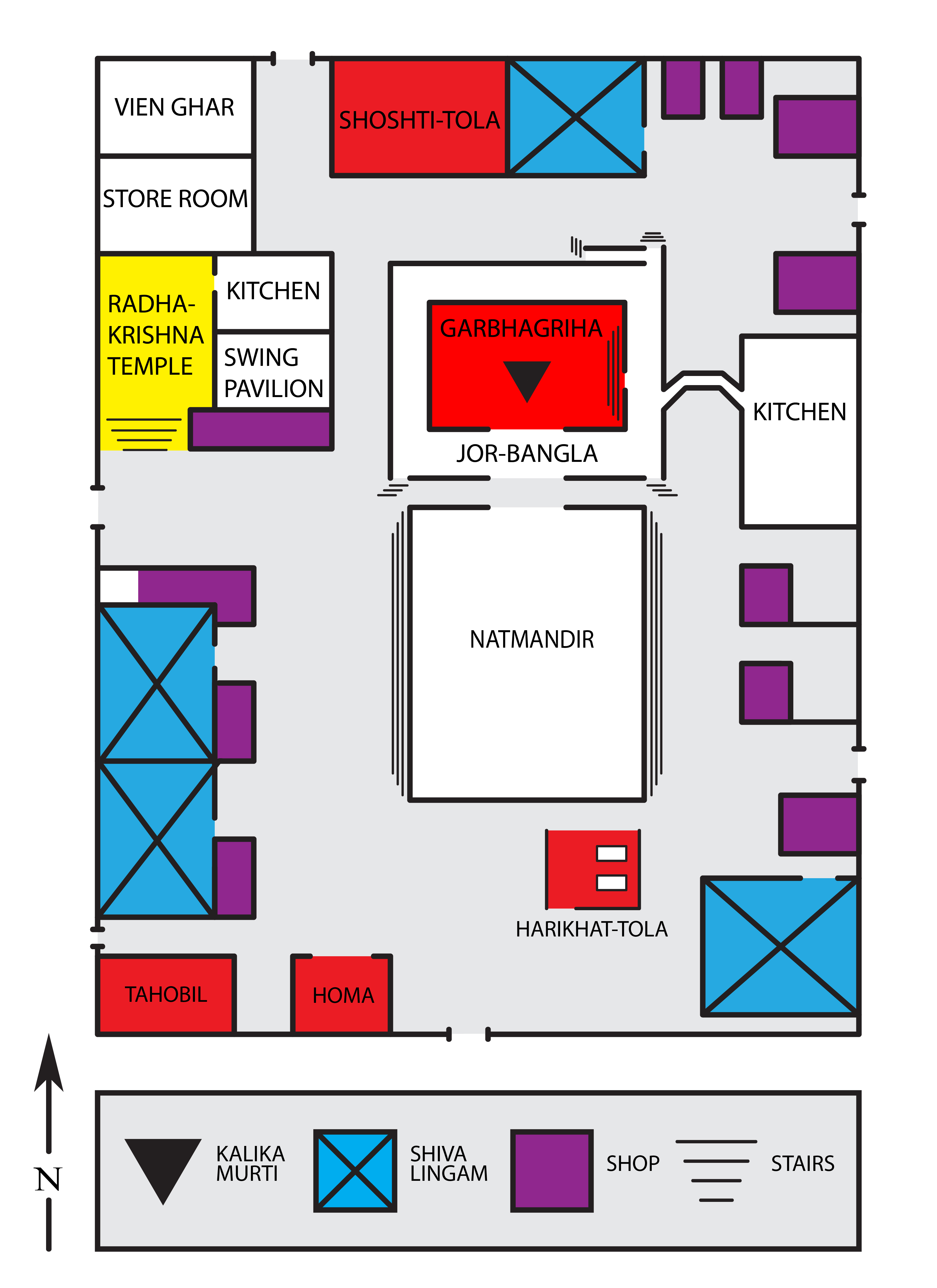

Map of the Kalighat temple complex (not to scale) created by William Clark. Based upon a drawing by Indrani Basu Roy and personal observations.

Kalighat Kali Mandir

The Kalighat Kali Mandir is a classic example of the Bengali architectural style which is a structural emulation of the mud and thatch-roofed huts of the villages. Kalighat’s main temple is a four-sided building with a truncated dome. A smaller identically-shaped projection caps this domed structure. Each sloping side of the roof is referred to as a chala, therefore the Kalighat Mandir is designated as an at-chala temple, its two roofs bearing a total of eight (at) separate faces (chalas). This stacked, hut-like design is common for Bengali temples and we find the same exact style of architecture used at another shakti pith examined on this website, the Tarapith Mandir (www.kalibhakti.com/tarapith).

Both roofs are painted a shiny, metallic silver and are decorated with bright bands of red, yellow, green, and blue where they join the building at the cornice. The uppermost roof is topped by three spires with the tallest central spire bearing a triangular pennant flag. Each of the mandir’s outer walls are decorated with a diamond chessboard pattern of alternating green and white tiles. A recent addition to the temple complex is the implementation of an elaborate lighting system which creates a novel mood and causes the mandir to glow with funky colors throughout the night.

Contained within the main mandir is the garbhagriha, the inner sanctum which houses the statue of the goddess. Large double doors on the southern side of the mandir open to reveal the interior to an attached, elevated veranda called the jor-bangla. The jor-bangla is a roofed, oblong pathway with openings on all four sides. Most pilgrims receive their darshan as they walk through the jor-bangla, looking down into the lower, innermost chamber of the Kalighat Mandir which houses the murti of Kalika. Stairs on each end of the jor-bangla direct the foot traffic through this passageway, which generally proceeds from west to east. While darshan is generally received from within the jor-bangla, another large aperture on its southern wall, allows devotees to look through it, from the vantage point of a specially constructed viewing stage called the natmandir.

The natmandir is a spacious rectangular pavilion located directly to the south of the garbhagriha. This roofed platform offers a less crowded and more relaxed setting than the jor-bangla for visiting devotees to receive darshan from a short distance. People can often be seen sitting cross-legged in the natmandir, with mala (prayer beads) in hand and counting mantras (sacred syllables, names, or phrases), or even conducting fire rituals. Closer to the temple complex’s periphery, the harikhat-tola (“sacrificial post area”) lies between the natmandir and the temple complex’s southern bounding wall. In addition to the areas described above, the temple complex also contains numerous auxiliary structures and stalls. These include several subsidiary shrines; a site for fire rituals; the tahobil where the sacrificed animals are butchered; two kitchens; stalls which sell flowers, sweets, incense, and other puja items; and an office for the Kalighat Temple Committee which oversee the affairs of the mandir. A map which I drafted can be found at the beginning of this section that will help with understanding the layout described in this essay.

The schedule of rituals that take place at the Kalighat Mandir follow a cyclical course which mirrors the circadian rhythm of human life. Kalika is viewed as a living goddess whose daily needs are attended to with the utmost reverence by her priesthood. Beginning at 4:00 am, she is gently awoken, after which her image is cleaned and decorated with garlands of red hibiscus flowers before the temple doors are opened to the public. At 6:00 am the elaborate ceremony of Kalika’s morning aarti begins. The doors to the garbhagriha remain open until 2:00 pm, when they are closed so that the pujaris can offer Kalika her food in private. For a period of time, the temple doors remain locked while the goddess eats and takes a nap. The prasad of this food offering is later distributed to temple employees, pilgrims, and local beggars. At 4:00 pm, the doors are again opened for devotees to commune with Kalika and have darshan with her murti. Some evening rituals, including a night time aarti, are performed before the garbhagriha’s doors officially close to the public around 11:00 pm. Kalika is then lovingly dressed and prepared for bed (Gupta 70-71).

[This footage of a Kalighat aarti provides an excellent view of the murti (Original Source Unknown)]

Kalighat is an extraordinarily busy temple where darshan generally begins by waiting in a long queue, only to be quickly pushed through the jor-bangla, while struggling against an eager and excited crowd for a glimpse of Kalika’s murti. Although a direct view of Kalika from the natmandir is theoretically possible, the line of vision is usually obscured by the large number of people who pack the jor-bangla. In order to facilitate darshan from the natmandir, temple officials periodically step into the crowded jor-bangla where they lock arms to form a human chain, forcefully prying apart the mass of devotees. The doorway of the sanctum sanctorum which opens to the jor-bangla is large enough to accommodate several temple officials (assistants of the phaledar) who stand in this opening at a strategic position to act as middlemen between the priests stationed within the garbhagriha, and the devotees in the veranda. Sometimes these middlemen will pull visitors up into this raised doorframe from where it is possible to have a bird’s eye view of the garbhagriha and a close look at the Kalika murti. It was only from this unique angle that I was able to examine the metalwork covering the garbhagriha’s double doors. There are five relief panels on both the left and the right doors which separately depict each of ten Mahavidyas––an esoteric cluster of Tantrik “Wisdom Goddesses.” The panel depicting the Mahavidya Kali was the only one daubed with orange sindoor. Below both columns of Mahavidya images were winged lions, a symbol associated with Shiva. I did not have much time to look around because after declining to pay the 500 rupees requested by one of the phaledar’s assistants, my head was quickly marked with orange sindoor (swiped from the Kali image) and I was asked to step back down into the jor-bangla.

Although the jor-bangla is where the majority of pilgrims receive darshan, there is a door on the Kali Mandir’s northeast side which permits direct access to the inner sanctum. Steps lead down into the garbhagriha wherein a path winding around the murti is delineated by fencing. Following this route takes you in a counter-clockwise direction until you find yourself face to face with the Kalika murti. A protective metal railing is erected around the back, right, and left sides of the statue. Each side of this barrier features the recurring motif of opposite facing swastikas flanking a coconut-topped pot––a group of symbols traditionally regarded as auspicious. If your arms are long enough, you can reach through this railing and touch the smooth black stone of the Kali murti. Generally, the line of devotees moves quickly through the garbhagriha, and soon you will find yourself face to face with the goddess Kalika, Kalighat’s beating heart.

The sacred image of Kalika is sculpted from a large, polished black stone. The only discernible facial features on the rock’s otherwise smooth surface are the nose and three eyes which project from it. These eyes are accentuated with a coating of brightly colored orange sindoor (pigment powder) paste. Attached to this stone murti are four arms made of silver. In accordance with iconographical convention, her left hands hold a khadga (sword) and a severed head, while her right hands display the mudras (hand gestures) of conveying fearlessness and offering boons. Another important attribute of the goddess––her lolling tongue––is represented here with a golden ornament. The precious metal has been hammered and shaped into the form of an extended tongue clenched by the upper row of teeth. The murti is further adorned with a silver crown, wrapped in sari cloth, and wreathed in numerous flower garlands. Kalika also wears necklaces of chain link, beaded with the cast metal heads of human males. These well-crafted, detailed embellishments combine with the monolithic black stone sculpture to create an image of the goddess that is both awe-inspiring and powerful to behold.

Kneeling before the murti to place my head at Kalika’s feet, I noticed another detail which would otherwise be easy to overlook. The statue rests upon a rectangular pedestal, the front of which is adorned with a silver relief of a supine Shiva. In anthropomorphic images of Kali, we typically find her standing upon her reclining husband, Lord Shiva. Here, in this more abstract representation, that aspect of her iconography has been cleverly incorporated into the base of the statue.

During my conversations with temple Brahmins, I was informed of another Kalika murti which is housed within the garbhagriha. It is a representation of the goddess considered so powerful that it is never displayed to the public, nor ever seen by the priests. This hidden image of the goddess was not fashioned with human hands, but was created by nature, and is therefore described as the self-generated, or svayambhu image of Kalika. Identified as one of the toes from Sati’s right foot, the adi rup (original form) is said to have fallen at this shakti pith, and is concealed within the pedestal upon which the Kalika murti stands. The silver reclining Shiva relief that I saw while placing my head at the goddess’ feet is, in fact, the decorative face of a lockbox containing the ancient form.

Kalika’s adi rup is removed on the full moon day of the Hindu lunar calendar month Joishtho (May 21 – June 22) when it is ceremonially washed for the annual occasion known as snanjatra (bathing festival). A highly secretive ritual takes place within the inner sanctum behind sealed doors, attended by only four members of the Haldar family. With great care, the original, svayambhu form of Kalika is removed from its lockbox by the shebaits who remain blindfolded throughout the entire proceeding; it is commonly held that this murti is too powerful for gaze of mortal eyes. Cloth wrapping from the previous year is carefully removed and Sati’s toe is bathed with a mixture of substances such as Ganga water and scented oils, before being freshly dressed and placed again within its protective enclosure. Devotees throng to the temple on this day, hoping to collect a piece of the older cloth wrapping or some of the goddess’ bottled snan-jol (bathwater)–items which are regarded as especially sacred (Roy 76 – 77).

Animal Sacrifice

The harikhat-tola (“sacrificial-post area”) of the Kalighat Kali Mandir is located on the southern side of the temple complex, between the natmandir and the outer wall. A concrete fence serves to obscure the sacrificial area from the view of casual onlookers and define the space within, where goats are beheaded as an offering to Kalika. Known as boli, the ritual immolation of goats has a long association with this temple. Entering the bounded space, one steps down onto concrete tiles set at a slightly lower elevation than the surrounding temple grounds. Within the enclosed area, there are two wooden forks, called harikhat, arranged side by side. Both of these harikhats are mounted on a rectangular base of concrete. In front of each, a portion of the otherwise tiled floor has been left open, exposing the ground below, where a mound of dirt serves to catch the khadga (ritual decapitation sword) as it swings down. This simple arrangement protects the blade by keeping it from dinting against a solid surface, thus preserving its sharpness.

I spent a good deal of time at the harikhat-tola where I regularly observed both sacrificial posts being offered red hibiscus flowers, incense, candles, coconut juice, curd, and fresh goat’s blood. A veritable mountain of incense ash is heaped in front of each harikhat where it ends up mixing with the effusion of liquid offerings to create a thick mud. Incense is lit by devotees upon entering the harikhat-tola, then waved around the sacrificial posts and toward the mandir as a salutation to Kalika. The wooden end of the incense sticks are then jammed into the ash mound and left to burn among numerous lit candles which have been similarly offered. Small clay lamps, known as diya, are also found lovingly placed around the harikhats, their burning cotton wicks fueled by the ghee (clarified butter) they have been filled with. Coconuts are cracked against the concrete bases of the harikhats with a loud ‘pop,’ and their juice is poured over the wooden posts. It is often said that coconuts are a “vegetarian” substitute for ritual decapitations as their round shape resembles a head, and the loud percussive noise they generate upon being broken is likened to the chopping sound of the khadga.

It is perhaps due to the misunderstandings of international tourists that photography is strictly prohibited within the Kalighat Temple complex. However, despite the posted signs forbidding photography, it is common to see Indian pilgrims taking commemorative pictures with their cell phone cameras––an understandably confusing situation for foreigners. During one early morning visit to the mandir at its 4:00 am opening time, my assistant Julie and I decided to follow the lead of others we saw and take a few pictures. Using her point-and-shoot digital camera, Julie took a photograph of me with my neck placed in one of the sacrificial harikhats. We were soon approached by a temple associate who kindly, yet firmly admonished us to not take any more photos and we respectfully complied. It is an unfortunate arrangement, but perhaps for the best, as graphic images of animal sacrifice have often been taken out of context and used to slander Hinduism. I was happy that we were able to maintain the good graces of the temple staff and still walk away with a photograph of me offering my head in a gesture of surrender to the goddess Kali.

It is important to note that the goats which are immolated at Kalighat do not go to waste; the meat from these sacrifices is later prepared and consumed as prasad (blessed offering). Popular tourist guides never fail to mention the animal sacrifices which take place at the harikhat-tola, yet categorically omit any reference to the nearby butchering station. The tahobil, located in the complex’s southwestern corner, is where the sacrificed goats are quickly and cleanly dressed for the animal’s donor to take home and cook. It seems that the reality of religious folks sanctifying the meat they occasionally consume makes for less titillating fodder than lurid tales of the “shocking” and “primitive” rites required to satiate a “bloodthirsty” deity. One goal of mine in examining the more sensationalized aspects of Hindu goddess worship is to offer objective documentation, to the best of my ability, so that in sharing this information I may hopefully dispel some common misunderstandings in the process.

The goat sacrifices at Kalighat generally proceed as follows. A young man adds an element of rhythm to the boli by playing a large dhak (barrel drum) with sticks throughout the rite’s duration. Depending on the size of the goat, one or two men take the animal, firmly holding its legs, then hoist it into the air to position its neck between the wooden posts. A peg is inserted into the harikhat to hold the goat’s neck in place, and the animal is decapitated with one downward swing of the khadga. This sequence of events, from start to finish, is over in a matter of seconds. According to ritual proscriptions, the head must be severed from the body with one blow––a rule which ensures a swift, humane end for the sacrificial animal.

While one goat per day is routinely sacrificed to prepare Kalika’s afternoon meal, a larger number of goat sacrifices take place on Tuesdays and Saturdays. Just like our western system, the Hindu calendar associates each day of the week with one of the seven classical planets. Beginning with Sunday, they proceed in the following order: Sun/Sunday, Moon/Monday, Mars/Tuesday, Mercury/Wednesday, Jupiter/Thursday, Venus/Friday, and Saturn/Saturday. Paradoxically, the two days considered most sacred to Kali––Tuesday and Saturday––correspond with the planets Mars and Saturn respectively, both of which are considered astrologically inauspicious.

In West Bengal, worship of the ever-creating, sustaining, and transforming goddess Kali has always been associated with blood sacrifice. At Kalighat, this practice is not only a daily requirement, but marked by a substantial increase on days identified with malefic planetary influences. While the rituals of the harikhat-tola and garbhagriha are distinctly separate affairs, both are vital components in the larger religious life of Kalighat, which illuminate different dimensions of this shakti pith’s presiding goddess. Within the harikhat-tola, the interplay of two important aspects of Kali’s personality––death and nourishment––is a directly observable phenomenon. The ancient practice of animal sacrifice in veneration of the life giving Mother Goddess underscores the transcendent position of Kali as a deity who exists beyond conventional notions of duality.

The Temple Complex

On the southern side of the Kalighat temple complex, between the harikhat-tola and tahobil, is a small lean-to containing a fire pit. When I asked a man who was seated cross-legged behind this pit and tending to its smoldering flame what this place was called, he responded with the words “Shiva Hom,” indicating that this area is used for a type of ritual, known as homa, where offerings are cast into a consecrated fire. It is notable that he referred to this fire pit specifically as the “Shiva Hom,” since it further emphasizes the presence of Lord Shiva, Kali’s consort, within the temple complex. In addition to Shiva’s homa, there are four lingam shrines within Kalighat’s surrounding walls. The largest and most prominent of these lingam shrines is found close to the harikhat-tola. Caution must be exercised when circumambulating the lingam enshrined within this small mandir. An assortment of sharp iron trishulas (“tridents”) haphazardly staked around the Shiva lingam jut out in all directions, making it easy to nick yourself (as I did) if you are not careful.

In addition to Shaiva and Shakta tradition, the Vaishnav current is also strongly represented at Kalighat. Although the temple complex they oversee is primarily regarded as a Shakta place of worship, the Haldar family––whose members have comprised Kalighat’s official priesthood for more than 250 years––are Vaishnavs by heritage (Roy 20). When the Haldars assumed control of the Kalighat Temple in the first half of the 18th century, the worship of Vaishnav deities was instituted within it’s bounds. Within the Kalighat Mandir’s garbhagriha, there is a concealed Vaishnav murti depicting a form of the god Krishna, called Basudev, who is the kuladeva (“clan deity”) of the Haldar family. Although the Basudev murti itself cannot be seen by visitors, the worship of Vaishnav deities assumed a public face at Kalighat when a Radha-Krishna shrine was built within the temple complex in 1843. The Radha-Krishna shrine (known as the Shyamoroy Mandir), is now the second most important place of worship within the complex, following after the main Kalika shrine. For the annual Vaishnav “swing festival,” the Radha-Krishna murtis are moved to an adjacent room where they placed on a swinging platform and gently rocked back and forth amid much festivities (Roy 11-12).

Another spiritually significant area within the temple complex is a tree shrine called the Shoshti-tola. This tree shrine is marked by the presence of three rounded stones, placed equally apart, which represent the goddesses Shoshti, Shitala, and Mongol Chandi. A unique feature of this sacred space is that it is only ever attended to by women. Typical worship at the tree shrine includes leaving a small donation of a few coins, and receiving a red forehead marking, called tilak, from one of the presiding priestesses. This tree shrine is also the samadhi (burial site) of Brahmananda Giri who is attributed with discovering the adi rup of Kalika in a nearby lagoon, called the Kundupukur (Roy 8).

Outside of the Kalighat temple complex’s bounding wall, directly to the southeast, is a sacred stepwell referred to as the Kundupukur. According to a Kalighat temple Brahmin who I spoke with, this is the location where the toes (one of which is Kalika’s adi rup) of Sati’s right foot were initially discovered. Today the Kundupukur is paved with concrete, but in ancient times it was a natural lagoon said to share a subterranean connection with the nearby Adi Ganga river. Surrounded by brick walls on all four sides, the Kundupukur is a rectangular pool which is used for ritual bathing by some devotees who visit Kalighat. On the Kundupukur’s eastern side is an octagonal pedestal upon which rests a marble sculpture of Lord Shiva meditating, which is given offerings of incense, kum kum powder, and flower garlands.

Other Sacred Sites

While the mandir which enshrines Sati’s fallen toe is undoubtedly the preeminent holy place of Kalighat, a constellation of temples found throughout the surrounding neighborhood further attests to the age and overall sanctity of this locality. For example, just outside of the Kalighat Kali Temple’s northeast entrance there are two shrines, both of which are filled with a number of divine representations including a large Shiva lingam, murtis of Hanuman, Rama, Durga, and a more-rarely seen idol of Kalki––the tenth and final avatar of Lord Vishnu.

Exiting the temple complex’s large western gate and bearing straight ahead will take you along a bylane that is flanked on opposite sides with numerous little shops and dotted with temples. This historically important route connects the Kalighat Kali Temple with the Adi Ganga River’s holiest landing stage, generally referred to as Mayerghat. It is the main ghat associated with Kalighat and the source of this locality’s name. Photographs and illustrations of Kalighat from the 19th and early 20th century depict this area as a busy thoroughfare, crowded with boats, as well as a place of attraction for large numbers of pilgrims who can be seen bathing in the sacrosanct water of the Adi Ganga. The Adi Ganga (literally “Original Ganges”) was once the course for the Hooghly River which is the largest tributary of the Ganges. The gradual shifting of the Hooghly over the years has left today’s Adi Ganga a shallow stream. Tragically, the river behind Kalighat suffers from extreme pollution and is essentially a dead canal. The surface of its nearly black, murky water glistens with an unnatural sheen; and a fetid, sulfurous smell indicative of sewage permeates the air surrounding it. This sad state has not gone unnoticed as local conservation efforts focused on reinvigorating the stream are underway––but years of dedicated effort will be required to bring the river back to life.

At Mayerghat, I noticed four murtis depicting the mythological couple, Savitri and Satyavan. These idols receive offerings of bright red kumkum (pigment powder) and prayers from married women seeking the longevity and well-being of their husbands. The story of Savitri and Satyavan is an ancient narrative, the earliest known version of which is recounted in the Hindu epic Mahabharata. In this tale, Savitri accompanied her husband Satyavan to the forest on the day that he was fated to die. The faithful wife took Satyavan’s head into her lap after he collapsed from weakness. There she awaited the arrival of Yama, God of Death, and a dialogue between them ensued. Yama was so charmed by Savtri’s display of wisdom, purity, and devotion that he restored the life of her husband. Along with offering kumkum to these murtis, women also take small pinches of the red powder to adorn their hair parting and left shankha (“conch shell”) bangle––symbols traditionally worn by Bengali women to signify marriage.

There is a cluster of small mandirs in the Mayerghat area, the most prominent of which are shrines dedicated to Shitola (goddess of smallpox), Jagganath (a form of Krishna), and Bagalamukhi (one of the Mahavidyas).

A short walk from the Kalighat Mandir, heading south along Kalighat Road, will take you to the Shahnagar Cremation Ground, located on the bank of the Adi Ganga. This extensive area is divided into two sections: on one side is an open air burning ground with two concrete fire pits, while the other contains an electric crematorium. Between these two sides is a lavish garden surrounded by tombs.The site where traditional open air cremations take place is a spacious, paved burning ground that contains a number of commemorative tombstones, a few large monuments, and an attached ghat. Although I have never personally witnessed corpses being burnt at this location, I was informed by locals that cremations do take place here. It is also a place of importance in the annual celebration of Kali Puja. During this festival, the goddess receives special attention at Shahnagar where a very tall murti of her cremation ground form, Smashana Kali, is installed in a temporary pandal. This holiday display draws flocks of devotees. When I visited Shahnagar on Kali Puja, the burning ground was crowded with people. Fires blazed in both of the pits which were surrounded by lit candles. At the edge of one pyre, a Tantrik clad in red garments was seated cross-legged, chanting with a mala in his right hand.

Within the burning ground is a tree shrine surrounded by a raised platform which is accessible via staircase. Bells hanging from an arch at the top of the stairs are rung by votaries who come here to pay homage. To the right of this tree shrine, at ground level, I noticed an altar of five human skulls arranged in a row, surrounded by melted wax leftover from previous candle offerings.

Off to one side of the cremation ground is a secluded area overlooking the river which contains a cluster of sacred sites. There is a small ashram (gathering place for spiritual activities) here, founded by a now deceased Tantrik guru, which houses a tableaux of murtis. The altar depicts Ma Durga accompanied by her attendants: Saraswati, Lakshmi, Ganesha, and Kartik. A tree shrine outside this ashram groups together a human skull, a metal statue of Ganesha, a lingam, and two trishulas.

A narrow path located on the southern side of the burning ground leads to a modest, yet highly cherished mandir, dedicated to an intriguing composite deity who combines West Bengal’s two most popular gods, Kali and Krishna, into one form. The murti at this small temple is aptly named Krishnakali. Although Krishna and Kali may at first appear to be contradictory, they are in fact often viewed by Bengalis as complimentary deities––a relationship which is readily apparent in the bhakti traditions of West Bengal. The names “Krishna” and “Kali” essentially mean “the dark one,” and despite their mythological differences, both deities are often paired together in Bengali devotional practice. The three most important Kali temples in Kolkata–Kalighat, Adyapith, and Dakshineswar–contain subsidiary shrines dedicated to Radha-Krishna. Likewise, it is common to hear Krishna’s mantra chanted at Kali temples. We also find Kali and Krishna paired together in Tantrik scriptures, as well as in the poetry of the Baul sect (who are usually aligned with Krishna bhakti) and Kali devoted Shaktas. An example of such correspondence can be seen in the following excerpt from the 18th century Shakta poet Ramprasad Sen:

Mother with disheveled hair has world-charming beauty ;

so I love Her black complexion …

Black complexion is the life of Vrindavana [Krishna’s sacred city], and makes the

milkmaids [the Gopis, Krishna’s lovers] indifferent to the world.

[Krishna] wearing a garland of wild flowers with a flute in

hand becomes Kali with a sword …

Prasada says, “When the knowledge of non-difference dawns,

black forms blend with one another” (Sinha 91).

Examples of the underlying unity between Kali and Krishna are far too numerous to mention here, but can be easily summed up in the words of one devotee I met while seated at the Shahnagar Krishnakali Mandir. As he explained it to me, Kali and Krishna are “two sides of same coin. Krishna is plus [+] power, and Kali is power.” The wide eyed facial expression he assumed when articulating Kali as “power,” seemed to indicate that whereas Krishna is positive power, Kali is the complimentary fearsome power.

Images of Krishnakali demand creativity as the artist must portray the idiosyncratic characteristics of two distinct deities, yet blend them into a harmonious form. At the Shahnagar Krishnakali Mandir, the artisan of the murti chose to depict the god as four-armed, displaying the abhaya mudra of fearlessness while holding aloft a sword and playing a flute. With a protruding tongue, garland of skulls, and feminine ornamentation, the murti seems more influenced by Kali’s iconography. Nevertheless, Krishna-specific symbols extend beyond the flute. Although obscured by a red sari, it is reasonable to assume that this murti’s lower half displays the cross-legged contrapposto stance characteristic of Krishna. The Krishnakali Mandir is regularly attended by a small, but dedicated congregation. The presence of a complex, composite figure like Krishnakali, located in the liminal space of the cremation ground associated with the Kalighat Mandir, further emphasizes Kali’s position as a deity of the crossroads.

Nakuleshwar Bhairav: Consort of Kalika

As with each of the fifty-one centers of power listed in the Mahapithanirupana, the goddess of Kalighat is associated with a specific male consort (Sirkar 36). The categorical Tantrik emphasis on the creative interplay of opposites finds its expression in the shakti pith mythos with the pairing of each Shakti with a local fierce manifestation of her husband Shiva. Coupled together like a lingam and yoni, the feminine power of Kalika is complimented by the masculine energy of Nokuleshwar Bhairav. While it seems that in many cases this convenient pairing of Shaktis and Bhairavs is somewhat arbitrary, the mandirs of Kalighat and Nakuleshwar Bhairav do share a marked degree of cohesiveness as both are controlled by the Haldar clan (Roy 5).

A short journey on foot or by cycle rickshaw will take you from the bustling atmosphere of the Kalighat Temple to the comparatively subdued home of Nakuleshwar Bhairav, located on nearby Haldar Para Lane. The Bhairav Temple’s interior consists of a large open room, the center of which is dominated by a raised marble platform that is roughly hexagonal in shape. At each corner of this six-sided platform, a decorative fluted pillar reaches to the ceiling. Circumambulating this mandir brings you to a shrine on the eastern wall that houses an approximately three foot tall stone murti of Shiva’s elephant-headed son, Ganesha. To the right of Ganesha are two sculptures of Shiva’s bull vahana (sacred vehicle), Nandi. Visitors to the temple give offerings of sindoor and marigold flowers to these deities.

In the middle of the temple’s central platform there is a large rounded opening, vaguely triangular in shape. Framed about with rectangular marble tiles, this hole is set down into the temple’s floor. Within this opening, the Shiva lingam that embodies Nokuleshwar Bhairav is housed and ritually worshipped. In order to touch this lingam, devotees must crouch low or lay flat against the floor and stretch their arms to reach into the opening. This lingam is a polished black cylindrical stone which rests in a concrete yoni base. A brass cobra, with its tail coiled around the lingam and it’s body extending upward, raises its hood to form a protective canopy above Nokuleshwar Bhairav. The yoni base slopes toward a channel which runs through the entire length of the mandir to the outside. This design is utilitarian, allowing drainage for the copious libations of water and milk which are routinely poured upon the lingam during ritual worship. Flowers, bilva leaves, incense, and other gifts are offered to Nokuleshwar. A temple Brahmin informed me that this mandir is 500 years old.

The Bazaar and Neighborhood of Kalighat

Because of the numerous sacred sites populating the Kalighat neighborhood, a thriving local economy has evolved in response to the regular influx of pilgrims. Both of the main roads leading to the Kalighat Kali Temple take you through the local bazaar, where the streets are lined with an assortment of shops and stalls. These tiny businesses sell a bewildering array of Kalika masks and statues, metal handicrafts, puja items, prayer beads, and books. Many shops in this market place also offer a large selection of the mass-produced “calendar art” prints, depicting a colorful myriad of Hindu deities, mythological heroes, and cultural icons in sizes ranging from postcard to poster.

This area is a veritable goldmine for anyone who collects devotional images. A modicum of digging will yield an incredible variety of pictures, some of which are quite old, or even occasional pieces of original artwork. Once, while I was chatting with the owner of a framing shop, my assistant Julie enthusiastically informed me that she found a Kalika screen print buried in a large stack of deity pictures. We proceeded to methodically comb through the shop’s numerous piles of devotional art and I ended up purchasing every original screen print we found.

Walking north from the mandir along Kalighat Road will take you through the infamous red light district located in the area around the Hazra Bridge. Long associated with illicit activities, this place is also notorious for the underground distribution of alcohol, an operation lasting well into the early morning hours. This red light area has a particularly nasty reputation which has led to Kalighat being regarded by some as a “dangerous place.” It was while walking through the red light area that I found one of my favorite local shrines to the goddess Ma Tara. There are a few musical instrument shops located in the area, as well as stalls selling puja items and floral wreaths. The shady business dealings which take place here remain safely hidden away behind the closed doors of the shanties lining the Adi Ganga. Despite the poor reputation of Kalighat’s red light district, there is no danger in walking through this highly-trafficked lane, and a visible police presence at the nearby intersection provides further reassurance.

CONCLUSION

As a place which encompasses a broad spectrum of extremes, Kalighat resembles its presiding goddess Kalika in many ways. Kolkata’s most historically important place of spiritual pilgrimage is a bridge between the ancient and modern–a dynamic microcosm that reflects the restless and ever-changing megacity of which it is an intrinsic part. Like a braided rope, the threads of Shakta, Vaishnav, and Shaiva tradition are intertwined at Kalighat, combining their individual strength and support. From the austere rituals of the garbhagriha to the spilling of blood, the currents of sacred and profane blend within the temple complex like the purifying and polluting waters of the Adi Ganga. Even the murti of Kalika––mass-produced in countless pictures, sculptures, and clay masks that are sold in the local bazaar––is itself a bridge between the concealed adi rup and the public. Kalighat, where families revere a goddess associated with society’s fringe, is the ideal home for the Krishnakali Mandir, dedicated to a transcendent figure who, like Kalika, simultaneously embodies “two sides of same coin.”

Kali is undoubtedly a complex goddess, perhaps most strongly characterized only by ambivalence. Her mythological and iconographical depictions appear to not only contain, but intentionally emphasize the contrary themes of creation and destruction, birth and death, and sacred and profane. It is precisely this contrast which has always been asserted by her most ardent and passionate devotees––the “madmen” who have come to be regarded as her saintly ambassadors: Ramprasad Sen, Bamakhepa, and Ramakrishna. The mystic-poet who forsook a life of privilege for one of poverty, the mad saint of Tarapith who freely mixed swear-words and drinking with his prayers, and the cross-dressing priest of Dakshineswar have all served, in various ways, to dramatically emphasize the liminal nature of their patron, the Mother Goddess.

To adopt the attitude of a child and approach Kali as the Mother, provides a way to reconcile those aspects of her personality which may otherwise seem to conflict with one another. Like nature and human existence, Kali is predictably unpredictable and devotion to her necessitates a direct confrontation with the harshest aspects of life––graphically represented by the severed head and sword she holds in her left hands. As the power of time, Kali is the great sacrificial fire into which all is ultimately offered. The ephemeral quality of our human existence and the inescapable reality of death forces us to make a choice: acceptance or denial. To embrace the here and now with open arms, and rejoice in the totality of existence which Kali circumscribes, is to take a radically life-affirming stance. While her destructive side is impossible to ignore, we cannot forget Kali’s equally powerful creative side––the hand gestures which assure us that we have nothing to fear and much to receive. Kali’s supreme boon––that of liberation––is not to be won by resistance, but through the cultivation of a “mad love” for the goddess who eternally generates, vivifies, and transforms all things. One does not have to physically decapitate themselves with a sword in order to offer their head to Kali––there is a gentler method of casting off the limitations of egoity. For the thousands of devotees arriving at Kalighat on a daily basis, it is enough to offer their surrender to the supreme source, who they simply refer to as “Ma.”

Works Cited

Gupta, Sanjukta. “Domestication of a Goddess.” Encountering Kali: In the Margins, at the Center, in the West. Ed. Rachell Fell McDermott and Jeffrey J. Kripal. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003.

Roy, Indrani Basu. Kalighat: Its Impact on Socio-Cultural Life of Hindus. New Delhi: Gyan Publishing House, 1993.

Sinha, Jadunath. Ramaprasad’s Devotional Songs: The Cult of Shakti. Calcutta: Sinha Publishing House, 1966.

Sircar, D.C. The Sakta Piths (2nd Rev. ed.). New Delhi: Motilal Benarsidass, 1973.

i love the picture with Maa kali and Sri krishna as one, first time I saw this. I always knew that they were one, this is my proof. thanks, keep up the great work.

Thanks so much for all of the positive feedback and for sharing the website with others. It means a lot to me. JAY MA KALI!

Mr.Clark you are really doing a great job.Mind blowing research and knowledge provided by you. I would be very glad to be in touch with you n your website.Kindly keep in touch through my mail id.Have good day waiting for your reply and new updates.

Thank you very much Saurabhji, I really appreciate the kind words. There will be many changes to the website in the near future and hopefully, in just a few months, I will be returning to India and continuing my research with Kali’s blessing.

Comment

Animal sacrifice is an evil practice.

I am not sure what you mean by ‘evil’ since it is such a loaded word. If you think that preparing and eating meat is an evil act, than you should focus your attention on industrial livestock production and factory farming where you live. Unlike the rite of boli, those practices result in the prolonged suffering of animals. If the goats were not eaten, I would agree with you. Otherwise I see nothing wrong with integrating the killing of an animal for food into one’s religious life since I do not separate the physical and spiritual aspects of existence.

Bordes Shwari Kali Mandir is a temple in Dhaka city at Rajarbag under Sabujbag Thana. It is near to Kamlapur railway station.

Hi there, Nice write-up. Likely to difficulty with all your web-site throughout website explorer, may possibly examination this specific? For example ‘s still industry head plus a significant part of individuals will pass up your impressive composing therefore trouble.

Our selected high profile independent escorts Delhi, Delhi escort girls understand that given services requires high values and maturity. Our rates are always checked to make sure. We are the most reasonable Delhi escort agency.

You can will discover, nevertheless, located in one computer software that likely will both

just as perform jailbreak As well as work out center. Such turnover coupled with decreased levels

along with proper protection can directed to risk

around my company’s familiarity base.

beautiful Celebrity, and simply smart escorts in can forever be retrieve at your service! We have the most amazing collection of bold Escort available for incall and outcall service. And not only they are picturesque and friendly � they are broad minded and want to give their clients full pleasure.

beautiful high profile independent escort in , and simply smart escorts in Bangalore can forever be retrieve at your service! We have the most amazing collection of bold Escort available for incall and outcall service. And not only they are picturesque and friendly � they are bold minded and want to give their clients authentic pleasure.

Greetings I am high profile independent escorts in, Model by Profession and Escort by Choice. I like change in life and want to enjoy it to its full extent. So Now I am here to host you. Like me few of my friends from fashion and modelling industry are also available For Escort Service in Bangalore.

Our independent escorts service is the service of unbeatable beauty and discretion a difference model escorts Delhi. Our clients believes on us just because of the excellent services provide by us with full satisfaction. We also serve the High class society people where maturity is must. Our high profile escorts will 100% cares about you and your desires. You must also ensure that the photos of the girls that you see online are recent and genuine. Our escorts are truly one of a kind each one is educated, a good conversationalist, sophisticated and charming, so you are not embarrassed to go out with them to a dinner.

Maa Kali blessing to all,jai maa bhadra kali

Our elite Delhi escort, Delhi escort girls know that given services requires high values and maturity. Our rates are always checked to make sure. We are the most reasonable Delhi escort agency.

Our selected Delhi escort agency, Delhi escort girls know that given services requires high values and maturity. Our rates are always checked to make sure. We are the most reasonable Delhi escort agency.

Terrific article. I became checking regularly this particular blog site and i’m impressed! Very handy information and facts in particular the final segment 🙂 I attend to similarly info a great deal. I was searching for this kind of data for a long time. Thank you and also of chance.

ウェブログあなたのレイアウトに|あなたのライティングスキルなどともに感心| 本当に非常 | 私は私は。それは自分|これは支払わテーマであるか、変更カスタマイズしましたか? いずれにしても このようなブログ| 素晴らしい素敵を見にまれ| | それはそれはだ、品質の書き込み優れた素敵を追いつきます。

送料無料 http://kadv.se/?class52=25408

I 常にこの読み取りに時間私の半分を過ごしたブログをウェブページの記事 毎日 | カップと一緒にすべての時間。

Hey Sir how your history of exploring the deep mystery began?what is your profession and area of interests? No doubt the comprehensive information you provided is remarkable and believable. And above all like a philosophical way to describe art history.

Thanks a lot

namaste

vijayanand from chennai. i am in search of kali ma. devotion to her praying to her makes me immensely satisfied. would like to meet you once i come to kolkata this year. please guide me in her worship. can i get your contact?

vijayanand

Very nice

please iwant jop

my name magdy

namaste, aapne bahot acchi jankari juta rakkhi hai,u r doing great job, mujhe kaali ghaat ke tantrik aashram ka contact no. chahiye tha… kya aap mujhe wo de sakte hai

I really liked your website…….

But I think you made a mistake…..

The necklace is supposed to be of heads of male demons, not male humans

Otherwise, loved the description…..

Dear William,

I came across your blog posts and I really like your observation and all the efforts you are making to understand your spiritual journey. I am a Kali Bhakt since age 15 and I am 29 year old in 2016. I would say that Kali Ma is not what is perceived by the Hindus, especially Tantriks. I have been chanting her mantra Om Krim Namah since age 15 and all I can say is that she is the mother, the creative energy of the supreme, the divine spirit which is the source of all the creation there is. I have never been to any temples and performed any animal sacrifices, because she is not only my mother but also the mother of every living being in the entire universe, in fact she is also the source of creation of inanimate objects. Her power is the electric energy, the Kundalini within each of us. She is the supreme, timeless and formless.

I have written this to you because I can feel the sincerity in your spiritual efforts. What I can advise you is that you do not try to understand her anymore or seek her in Hindu rituals, she is nowhere in there. If you are chanting her mantra, then continue that but not more than 10 minutes and make a list of all the things you are really grateful for. An example of a sentence is Thank you Ma for all the wonderful people I come across. Make a list of around 600 such sentences and then read this list once a day everyday. You will start receiving the guidance in your spiritual practice. She lives in your heart and that is where she lives in every single being, but it is only that her devotees acknowledge her presence within them and then continue on the magical journey being guided by Ma.

I have written this email because Ma has asked me to, but you always have a choice. If you want to follow my advise you can or just ignore this email and continue on your journey. All I can say is She doesn’t need your blood, nor your flesh, nor your life, she wants you to become perfect just like her, original just like her, she hates obscurity. She is waiting to guide you on your journey, do her mantra and read your lists everyday, you will understand everything you need to know about her. You will for sure know that with her power you become timeless, spiritual and that she only wants the best for you.

My guru who gave me the mantra told me that never sacrifice animals to Kali, she is the mother of the entire universe, every being is as dear to her as much as you are. Love is the other name of Kali.

Hi, sister Gayatri I want to can you gave your email Thanks, or fb id

Hi blogger i see you don’t earn on your site. You can earn additional money easily, search on youtube for:

how to earn selling articles

8395806895

very nice blog and jai maa kaali

It is possible to see Kali Maa face to face but only if we have devotion like Sri Ramakrishna. Sri Ramakrishna was mad in love for Devi Kali Maa and he will offer food to Kali before eating any food himself.

Download the pdf file the-gospel-of-ramakrishna.pdf to read in detail the life of Sri Ramakrishna Paramhansa

@Trevor – Animal sacrifice is an evil practice.

Correct – How can a person ask for happiness for himself and place an animal in severe trouble by killing it. If we do this then it surely show our ignorance and foolishness.

I AM HIGHLY THANKFUL TO YOU TO GIVE ME A SCOPE TO SEE MY SUBPRIME BRAMBHA